9 Jan 2026

- 10 Comments

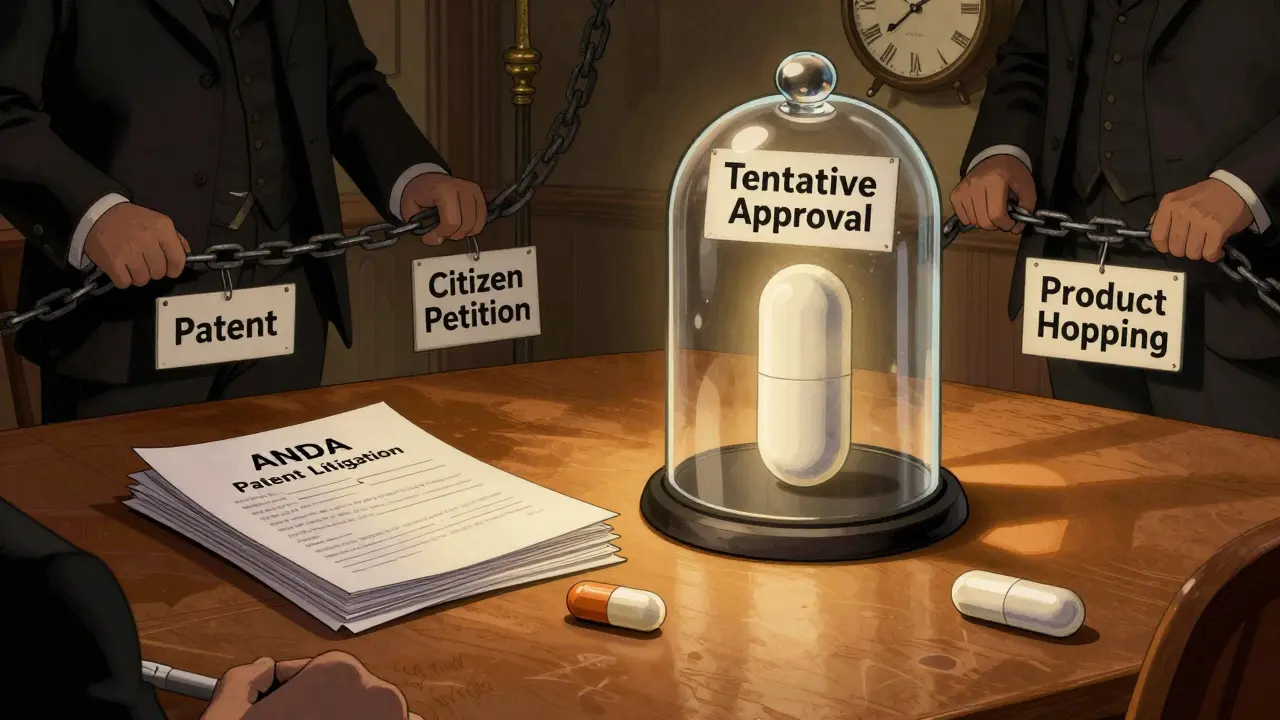

Every year, the FDA grants tentative approval to hundreds of generic drugs. These aren’t just paperwork wins-they’re lifelines waiting to happen. A tentatively approved generic has passed every scientific test: it’s safe, effective, and matches the brand-name drug in strength, dosage, and how the body absorbs it. So why do so many of these drugs sit on the shelf for years after approval? The answer isn’t one thing. It’s a tangled mix of patents, paperwork, profit, and process.

What Tentative Approval Actually Means

Tentative approval isn’t a half-step. It’s a full pass-just with a legal lock on the door. The FDA gives this status when a generic drug maker submits an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) and clears every hurdle: chemistry, manufacturing, bioequivalence, labeling. Everything checks out. But the FDA can’t let the drug hit the market yet because a brand-name drug still holds patents or exclusivity rights.

This system was built by the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. It was supposed to speed up access to cheap drugs. Instead, it created a waiting room where generics sit, ready to go, while legal battles drag on. As of 2023, over 2,500 generic applications had received tentative approval. But only about half ever made it to pharmacy shelves.

Patent Games: The Biggest Roadblock

The single biggest reason tentative approvals don’t turn into real drugs? Patent litigation.

When a generic company files an ANDA, it often certifies that the brand’s patents are invalid or won’t be infringed. That’s called a Paragraph IV certification. And when the brand company sees that, they almost always sue. And when they sue, the FDA is legally blocked from giving final approval for up to 30 months. That’s not a suggestion. It’s a court-ordered pause.

Between 2010 and 2016, 68% of tentatively approved generics were stuck because of these lawsuits. Even if the generic wins the case, the delay eats up time. By the time the court rules, the patent may have expired, but the market has already moved. Competitors may have launched. Prices may have dropped. The original generic maker might decide it’s no longer worth the cost to launch.

Then there’s the ‘citizen petition’ trick. Brand companies file petitions with the FDA, asking them to delay approval on technical grounds-like claiming the bioequivalence study method is flawed. Between 2013 and 2015, the FDA received 67 of these petitions from brand companies. Only three were granted. But here’s the catch: the FDA has to respond. And while they’re responding, the clock keeps ticking. One study found petitions filed within 30 days of patent expiration delayed generic entry by an average of 7.2 months.

And don’t forget ‘product hopping.’ Some brand companies make tiny changes to their drug-switching from a pill to a liquid, changing the release mechanism-and then get a new patent. This pushes back the clock on generic entry. The FTC found this happened with 17% of top-selling drugs.

Manufacturing Problems: It’s Not Just About the Drug

Even if patents clear, the drug still needs to be made. And making it right is harder than most people think.

Generic drug makers don’t always have the same resources as big pharma. Their factories might be older, understaffed, or under-audited. The FDA finds problems in 41% of the complete response letters (CRLs) they send out-letters that say, ‘Your application isn’t approved because of manufacturing issues.’

The top three problems? Inadequate quality control systems (63% of facility-related CRLs), poor environmental monitoring (29%), and unqualified equipment (24%). These aren’t small mistakes. They’re system failures. If a factory can’t prove it can consistently make a drug that won’t degrade or get contaminated, the FDA won’t sign off.

Complex drugs make this worse. Inhalers, creams, injectables, extended-release pills-they’re harder to copy. They need more testing, more validation, more time. One study showed complex generics go through 2.3 times more review cycles than simple pills. And when the FDA sends back a CRL, the clock doesn’t stop. The company has to fix the problem and resubmit. On average, they take 9.2 months to respond-nearly double the recommended 6 months.

Bad Applications: The Paperwork Trap

Too many generic applications are just… incomplete. Not because the company is lazy, but because the requirements are dense, shifting, and confusing.

In 2021, the FDA found that 29% of initial ANDA submissions had major gaps: missing stability data, unclear labeling, or flawed chemistry sections. By 2022, 43% of all deficiencies were tied to stability testing-how the drug holds up over time under heat, humidity, and light. Another 31% were about the container and closure system-why does the pill bottle matter? Because if the packaging lets moisture in, the drug breaks down. And if it breaks down, it’s unsafe.

These aren’t edge cases. They’re routine. And they cause delays that add up. Before the FDA started tracking this under GDUFA (Generic Drug User Fee Amendments), it took nearly four review cycles to approve a generic. Even after GDUFA’s reforms, the average was still 3.2 cycles in 2022. Each cycle means months of back-and-forth.

Money Matters: Sometimes, It’s Just Not Worth It

Even if the patent clears, the factory passes inspection, and the paperwork is perfect-some generics still never launch.

Why? Because the market isn’t profitable enough.

A 2022 analysis found that 30% of tentatively approved generics never hit the market. That number jumps to 47% for drugs with annual U.S. sales under $50 million. If a drug only sells $20 million a year, and the generic maker expects to get 10% of the market at $0.10 per pill, the profit margin might not cover the cost of scaling up production, hiring staff, or navigating distribution.

And if only one generic enters the market, prices stay high. A 2019 study found that even after a generic launches, prices remain at 80% of the brand’s price for two full years if there’s only one competitor. So other companies wait. They don’t want to rush in and get crushed by low prices. That’s called ‘first-mover disadvantage.’

For complex drugs like inhalers or topical creams, the problem is worse. Manufacturers need special equipment. Training. Validation. It takes longer. And by the time they’re ready, the window of high profit may have closed. The FDA found that 62% of these complex generics faced launch delays over 12 months-even after patents expired.

What’s Being Done? Progress, But Slow

The FDA knows this system is broken. They’ve tried to fix it.

The Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT) pathway, created in 2017, fast-tracks drugs with little or no generic competition. In 2022, 78% of CGT-designated drugs got tentative approval in just 8 months-compared to the usual 18. That’s real progress.

The FDA also launched a 2022 initiative to prioritize 102 high-need tentatively approved drugs. Of those, 67% received final approval within 12 months, compared to only 34% in the general group.

But the big challenges remain. The FDA’s own 2023 report says: ‘Ongoing challenges with complex product development, patent litigation strategies, and resource constraints will continue to impact tentative approval timelines through at least 2025.’

Legislation like the CREATES Act (2019) tries to stop brand companies from blocking generic makers from getting samples of the brand drug-something they need to test against. But enforcement is weak. The Affordable Drug Manufacturing Act (2023) aims to help small manufacturers build new plants. But it’s still early.

What’s the Real Cost?

Every month a generic is delayed, Americans pay more. The Congressional Budget Office estimated patent-related delays added $9.8 billion to drug spending in 2018. By 2027, that number could hit $12.4 billion.

And it’s not just money. It’s access. People who need insulin, blood pressure meds, or antibiotics wait longer because the cheaper version is stuck in legal limbo. Doctors prescribe the brand because it’s the only one available. Patients pay hundreds more a month. Families skip doses. Hospitals ration.

Tentative approval was meant to be a shortcut. Instead, it became a maze. The science is there. The manufacturing can be done. The law is supposed to help. But the system is still tilted toward the brand companies that can afford to fight.

Until patent abuse is curbed, factories are properly funded, and applications are submitted right the first time, tentative approval will remain a promise-not a pathway.

Ashlee Montgomery

January 11, 2026Tentative approval feels like being handed a key to a car that’s still in the impound lot. The engine’s perfect, the tires are new, but someone’s got the title locked in a vault. We’re not waiting for innovation-we’re waiting for lawyers to finish their coffee breaks.

neeraj maor

January 12, 2026Let’s be real-the FDA’s just a puppet. Big Pharma owns the patents, the courts, and the FDA’s budget. They don’t want generics because generics kill margins. This whole system is a legal shell game designed to keep prices high. The ‘citizen petitions’? Pure theater. They file them knowing the FDA will take months to respond. That’s not regulation-that’s extortion with a stamp.

Ritwik Bose

January 13, 2026While I deeply appreciate the thoroughness of this analysis, I must respectfully acknowledge the structural complexities involved in pharmaceutical regulation. The balance between innovation incentives and public access remains a delicate equilibrium, and while delays are regrettable, they are often rooted in legitimate safety concerns. Perhaps a more collaborative framework between stakeholders could yield sustainable progress. 🙏

Paul Bear

January 14, 2026Let’s not romanticize the ‘generic manufacturer’ as some noble underdog. Most ANDA submissions are sloppy. The 29% deficiency rate? That’s not regulatory overreach-that’s poor quality control. If you can’t submit a clean application, don’t cry when the FDA sends it back. And yes, Paragraph IV certifications are tactical, but they’re also a legal right. The problem isn’t the system-it’s the actors who don’t do their homework.

lisa Bajram

January 14, 2026Y’ALL. This isn’t just about pills. It’s about grandmas skipping insulin because they can’t afford the brand. It’s about veterans with PTSD paying $300 for a $5 generic that’s been sitting in legal purgatory for 4 years. The FDA’s got a ‘Fast Track’ label like it’s a Starbucks reward. Meanwhile, people are choosing between rent and refills. And the ‘complex drugs’ excuse? Please. We’ve got the tech. We’ve got the science. We just don’t have the will. This is a moral failure wrapped in regulatory jargon.

Jaqueline santos bau

January 15, 2026Okay but have you seen the factories in India? The ones making half the world’s generics? I’ve seen videos-dust everywhere, workers in flip-flops, no gloves, no air filtration. And you’re telling me we should trust these pills? The FDA’s slow because they’re trying to stop poison from reaching American kitchens. This isn’t bureaucracy-it’s triage. And if you think the brand companies are the villains, you’re not looking at the whole picture.

Kunal Majumder

January 16, 2026My cousin works in a generic lab in Hyderabad. They spent 18 months fixing one stability issue just to get a CRL cleared. No one talks about how hard these teams work. It’s not lazy-it’s painstaking. And when the FDA changes its guidance mid-process? That’s when you lose a year. The system breaks people, not just drugs.

Aurora Memo

January 17, 2026It’s heartbreaking how many lives are delayed by paperwork. But I also wonder-what if we invested in training more reviewers at the FDA? Or created a public database of common deficiencies so manufacturers could learn before submitting? Small fixes, done with care, could move the needle without burning anyone out.

chandra tan

January 18, 2026Back home in Kerala, we get generics for pennies. No patents, no drama. But here? We’ve turned medicine into a chess game where the board is rigged. The real tragedy? The people who need these drugs the most don’t even know they exist. They just see a $200 co-pay and give up.

Dwayne Dickson

January 20, 2026So let me get this straight: the system is designed to incentivize innovation, but the incentives are being weaponized to suppress competition? And we’re surprised that prices stay high? The CREATES Act is a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage. The real fix? End patent evergreening. Ban product hopping. Strip away the 30-month stays. Or better yet-let the FTC sue the brand companies into oblivion. This isn’t healthcare policy. It’s corporate rent-seeking with a stethoscope.