22 Nov 2025

- 8 Comments

When you walk into a pharmacy in Australia and pick up your prescription, you might pay just $7.70 or $31.60 - no matter if it’s a heart medication, diabetes drug, or antibiotic. That’s not magic. It’s the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), one of the most powerful tools in the world for making medicines affordable. And at the heart of this system? Generic drugs. They’re not just cheaper alternatives - they’re the engine that keeps the PBS running, saving Australians billions every year.

How the PBS Works - And Why Generics Matter

The PBS isn’t just a subsidy program. It’s a government-backed price control system that negotiates how much pharmacies pay for medicines, then passes the savings to patients. The government covers about 90% of the cost. You pay the rest - a co-payment. In 2025, that’s $31.60 for most people, and $7.70 for those with concession cards. But here’s the key: the PBS doesn’t pay the full price of the drug. It pays the subsidized price - and that’s where generics come in. Generics are chemically identical to brand-name drugs but cost far less. In Australia, 84% of all prescriptions for off-patent medicines are generics - the highest rate in the OECD. Why? Because the PBS uses a system called reference pricing. If five drugs treat the same condition, the government sets the subsidy based on the cheapest one. If you choose a more expensive brand-name version, you pay the difference out of pocket. That pushes pharmacists and doctors toward generics - and patients toward savings. This isn’t theoretical. In 2024, generic medicines made up 46% of total PBS spending, even though they represent the vast majority of prescriptions. That’s because a single generic pill might cost $0.50, while the brand version costs $5. Multiply that by millions of prescriptions, and you’re talking billions saved.The Players Behind the Scenes

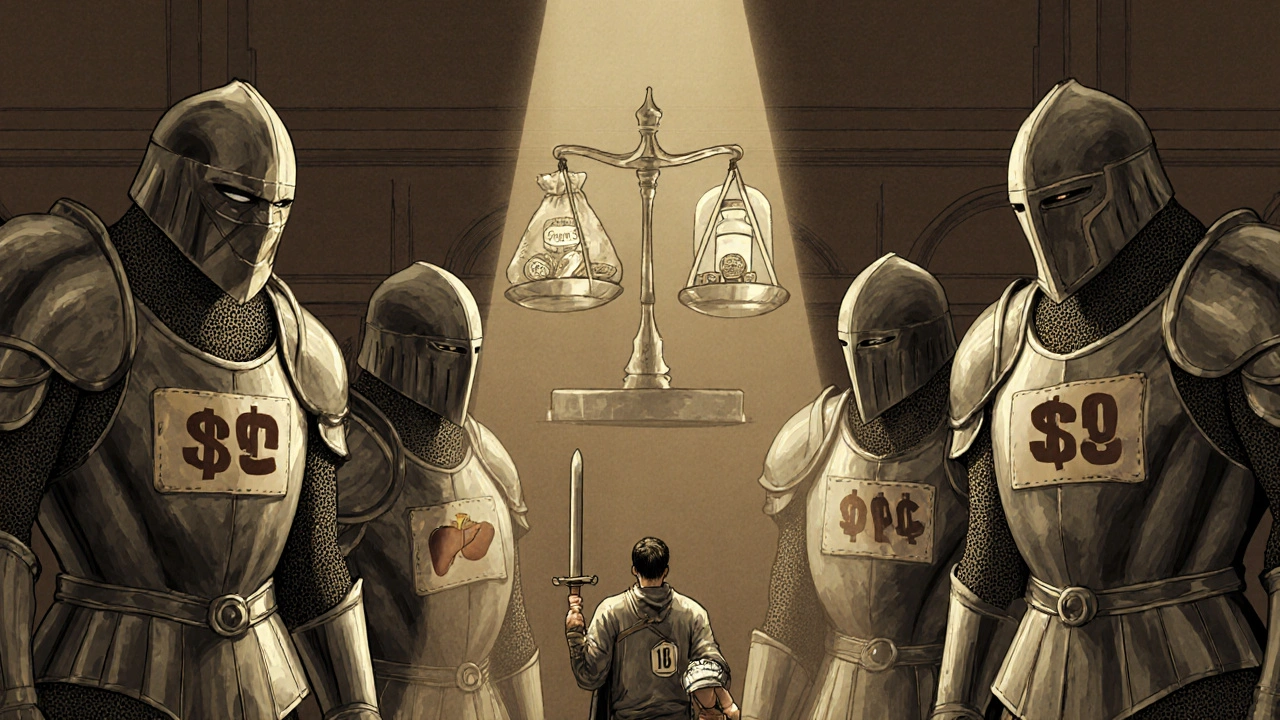

You don’t see them, but five companies control nearly two-thirds of Australia’s generic market: Symbion, Sigma, Mylan, Aspen, and Hospira. These aren’t small players. They’re global manufacturers with factories in India, Europe, and North America. They compete fiercely on price - and the PBS rewards them for it. The rules changed in 2020. After a generic enters the market, the PBS cuts the reference price to 60% of the original brand’s price after six months. After a year, it drops to 43%. That forces manufacturers to slash prices fast - or get left behind. The result? Within 12 months of multiple generics entering, the average price of a drug falls by 62%. In heart medications, the drop is even steeper - 74%. But not all drugs follow the same path. Biologics - complex drugs made from living cells, like those for rheumatoid arthritis or cancer - are harder to copy. Substitution rules are stricter, and generics (called biosimilars) take longer to catch on. Only 63% of biologic prescriptions are filled with generics, compared to 95% for statins. That’s where the PBS still has work to do.Who Benefits - And Who Gets Left Behind

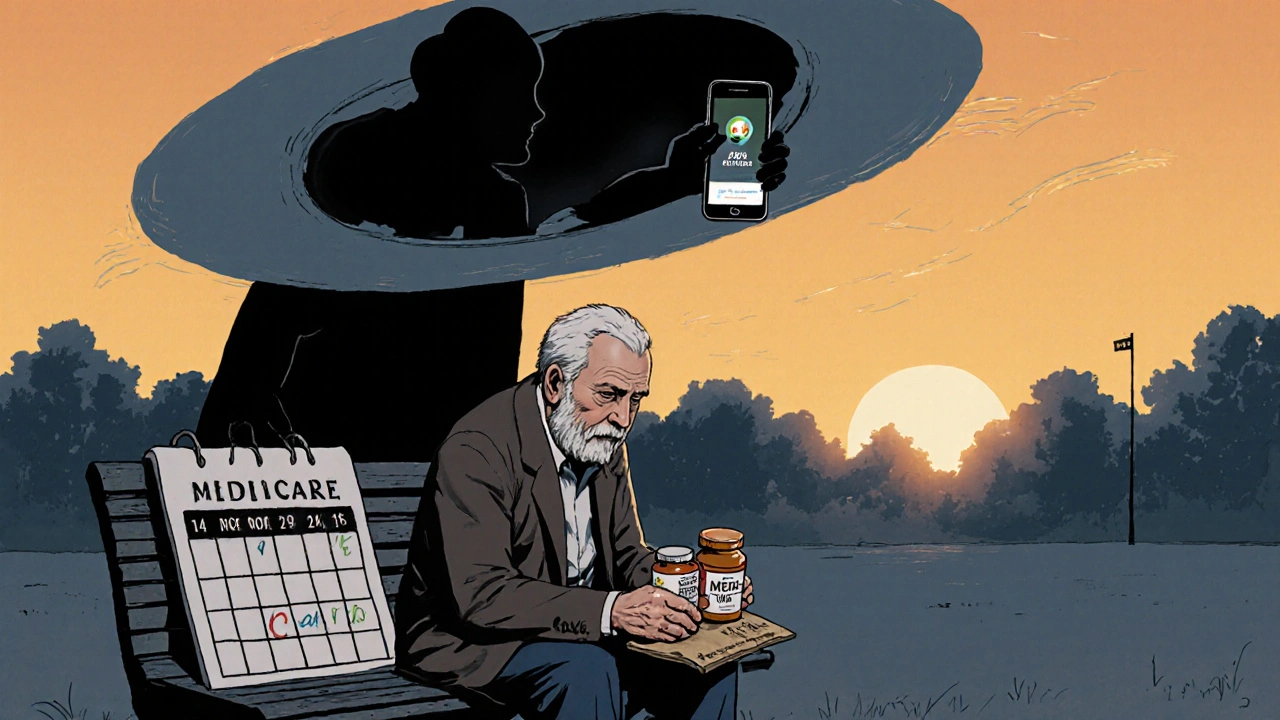

The PBS is designed to be fair. But real life isn’t perfect. Concession card holders - seniors, low-income families, disability recipients - pay $7.70 per script. They can get a 60-day supply for the price of one co-payment. That’s a 50% saving. For someone on five medications, that’s $38.50 a month instead of $77. But general patients - working adults without concession status - pay $31.60 per script. That adds up fast. Five prescriptions? $158 a month. One in eight general patients admit they skip doses or don’t fill prescriptions because they can’t afford it. Reddit threads from self-funded retirees are full of stories: “I choose between insulin and groceries.” “I cut my pills in half to make them last.” The PBS safety net helps. Once you spend $1,571.70 on co-payments in a year, your co-payment drops to $7.70 for the rest of the year. But hitting that threshold takes time. For someone on multiple expensive drugs, it can take 8-10 months. That’s eight months of financial stress. And then there’s the “PBS black hole.” A drug gets approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) - that’s the safety check. But it can take over 14 months to get listed on the PBS. During that time, patients pay full price - often $1,850 or more for a single course of treatment. That’s not just expensive. It’s life-threatening for people with chronic conditions.

Why Australia’s System Is Different

Compare Australia to the U.S. There, a month’s supply of insulin can cost $300. In Australia? $31.60. That’s because the U.S. lets drugmakers set their own prices. Australia doesn’t. The PBS uses a cost-effectiveness gatekeeper: the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC). They don’t just ask, “Is this drug safe?” They ask, “Is it worth it?” They use a metric called QALY - quality-adjusted life year. If a drug costs more than about $50,000 per QALY, it’s unlikely to be listed. That sounds cold, but it keeps the system sustainable. Other countries are stricter. The UK’s NICE uses a £20,000-£30,000 per QALY cap. Canada’s PMPRB caps prices but doesn’t evaluate effectiveness. Australia walks a middle path. It’s flexible. It’s allowed drugs costing over $150,000 per QALY for rare diseases - if they meet the Highly Specialised Drugs Program (HSDP) criteria. But that flexibility has a cost. The median time from global launch to PBS listing is 587 days. In Germany, it’s 320 days. In Canada, 410. That delay costs patients money, time, and sometimes lives.What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

The government is trying to fix the cracks. In January 2026, the general patient co-payment drops from $31.60 to $25.00. That’s a $6.60 cut - $784 million saved by patients over four years. But it also means the government will pay more. The PBS budget is already $13.5 billion. By 2030, it’s projected to hit $18.7 billion, mostly because of expensive new cancer and autoimmune drugs. The HSDP is being relaxed. Two of its eight criteria for rare disease drugs are being removed. That means more patients with ultra-rare conditions will get access - faster. New drugs like Talazoparib for prostate cancer and Relugolix for endometriosis were added to the PBS in 2025. That’s 150,000 more Australians getting subsidized treatment. Digital tools are rolling out too. The PBS app has been downloaded 1.2 million times. Pharmacists can now submit authority requests electronically. Processing time? 1.8 days. Paper? 7.3 days. That’s progress. But the biggest challenge remains: slowing down the cost of new medicines. Biologics, gene therapies, personalized cancer treatments - these aren’t going away. They’re getting more expensive. The PBS can’t keep subsidizing them at current rates without raising taxes or cutting other health services.

What This Means for You

If you’re an Australian with a Medicare card, the PBS is your invisible safety net. It means you can get life-saving drugs without going broke. But it’s not flawless. You might still face delays, confusing rules, or co-payments that hurt. If you’re on multiple medications, know your safety net. Track your spending. Once you hit $1,571.70, your co-pay drops. That’s a game-changer. If you’re a prescriber, use the PBS tools. The online portal and app can save you hours. Know which drugs require authority - and why. It’s not bureaucracy. It’s about controlling costs so everyone can get what they need. And if you’re a patient without a concession card - you’re not alone. Talk to your pharmacist. Ask about generic alternatives. Check if your drug is on the PBS. Call 1800 020 299. There’s help. The PBS isn’t perfect. But it’s one of the few systems in the world that actually works for ordinary people. Generics keep it alive. And without them, Australia’s health system would collapse under the weight of drug prices.That’s the real impact: not just lower prices - but access. For millions, the PBS means taking their medicine. Not choosing between it and rent. Not skipping doses because they can’t afford the next script. That’s what matters.

How much do I pay for PBS medicines in 2025?

As of July 2024, general patients pay $31.60 per prescription, and concession card holders pay $7.70. These amounts are indexed annually to the Consumer Price Index (CPI). However, the general co-payment will drop to $25.00 on January 1, 2026, under the National Health Amendment (Cheaper Medicines) Bill 2025. Both rates apply per script, regardless of the drug’s actual cost.

What is the PBS safety net and how does it work?

The PBS safety net protects patients who spend a lot on prescriptions in a calendar year. Once you’ve paid $1,571.70 in co-payments (as of 2025), your co-payment drops to $7.70 for the rest of the year - even if you’re a general patient. This applies to all PBS-subsidized medicines. Concession card holders reach the safety net faster because their co-payments are lower, and they’re already at the reduced rate.

Why are some medicines not on the PBS?

Not all medicines make it onto the PBS because they must pass the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee’s (PBAC) cost-effectiveness review. The PBAC evaluates whether a drug provides enough health benefit (measured in QALYs) for the price. Drugs that are too expensive relative to their benefit - or lack strong clinical evidence - are not listed. Some are also too new; the average time from global launch to PBS listing is 587 days.

Can I get generics even if my doctor prescribes a brand name?

Yes. Pharmacists in Australia are legally allowed to substitute a brand-name medicine with a generic equivalent unless the doctor writes "Do Not Substitute" on the prescription. Even if your script says the brand name, the pharmacist can give you the cheaper generic version - and you’ll still pay the same PBS co-payment. This is standard practice and encouraged under the PBS reference pricing system.

How does the PBS compare to drug pricing in the U.S.?

Australia’s PBS system is dramatically cheaper than the U.S. For example, a 30-day supply of insulin costs about $300 in the U.S. but only $31.60 (or $7.70 for concession holders) in Australia. Generic medicines in Australia cost 30-40% less than in the U.S., according to OECD data. The U.S. has no national price negotiation system - drugmakers set prices freely. Australia negotiates prices directly with manufacturers and uses reference pricing to drive down costs.

What’s the difference between a generic and a biosimilar?

Generics are exact copies of small-molecule drugs (like aspirin or metformin). Biosimilars are similar, but not identical, copies of complex biological drugs (like Humira or Enbrel), which are made from living cells. Because they’re more complex, biosimilars take longer to develop and approve. They also face stricter substitution rules - pharmacists can’t automatically swap them without the doctor’s approval. That’s why only 63% of biologic prescriptions use biosimilars in Australia, compared to 95% for simple generics like statins.

How do I know if my medicine is on the PBS?

You can check the PBS website (pbs.gov.au), which is updated monthly with new listings. You can also use the Services Australia PBS app, which lets you search for medicines and see your co-payment amount. If your medicine isn’t listed, you’ll pay full price. Ask your pharmacist or doctor to check for you - they have access to the same tools.

Why do some prescriptions need authority approval?

Authority-required prescriptions are for medicines that are expensive, have strict usage rules, or are used for specific conditions. Examples include certain cancer drugs, high-cost antibiotics, or treatments for rare diseases. The PBS requires prior approval to ensure the drug is being used correctly and only when medically necessary. Over 28% of PBS listings require authority approval, and this process can delay treatment by days or weeks - especially if submitted on paper instead of electronically.

james lucas

November 22, 2025so like i just found out my insulin is $31.60 here and in the states its like 300??? like wtf man. i mean i knew prices were wild but this is next level. my cousin in texas is cutting her pills in half and its not even a joke. this system is actually kind of insane in the best way

Mark Williams

November 24, 2025The PBS reference pricing mechanism is a textbook example of demand-side cost containment via therapeutic substitution. The 84% generic utilization rate among off-patent agents reflects strong policy alignment with pharmacoeconomic efficiency. What’s underappreciated is the elasticity effect-when reference pricing drops to 43% after 12 months, manufacturers are forced into a race-to-the-bottom on marginal cost, which in turn increases volume penetration. The QALY threshold of ~$50K is pragmatic, though it risks excluding high-benefit, low-volume innovations unless HSDP accommodations exist.

Ravi Kumar Gupta

November 24, 2025Bro, I work in a pharma plant in Hyderabad and I’ve seen the pills you’re paying $0.50 for. We make them in 100 million batches. The brand name? Same pill, same factory, different label, 10x markup. Australians are getting ripped off in the best way possible. The PBS is the only thing keeping the global generic market alive. USA? They pay for the marketing, not the medicine. Shame.

Jessica Correa

November 25, 2025i just had to pay $31.60 for my blood pressure med and honestly i cried a little because in my old job i couldnt afford it at all. the safety net thing is a lifesaver but it takes so long to get there. i wish they made it easier to track. also i had no idea pharmacists could switch to generic without asking. that feels like magic

Miruna Alexandru

November 26, 2025It’s not ‘magic’-it’s rationing disguised as benevolence. The PBS doesn’t make drugs affordable; it makes them unprofitable for manufacturers, which forces consolidation into five global oligopolists. The QALY metric is a cold calculus that devalues life based on statistical utility. And the 14-month PBS black hole? That’s not a delay-it’s a death sentence for patients with progressive conditions. This isn’t healthcare-it’s actuarial control.

Rahul Kanakarajan

November 28, 2025Bro you guys are lucky. In India, generics are everywhere but half of them are fake. I’ve seen people die because they bought fake metformin from a roadside shop. Australia’s system is clean because the TGA actually checks stuff. But you still pay $31.60? That’s still too much if you’re on five meds. My uncle in Delhi pays $0.20 for the same pill. But he also doesn’t have a doctor checking if it’s safe. So… trade-offs, right?

Daniel Jean-Baptiste

November 28, 2025just got my new script for that biologic and yeah its still $1800 out of pocket because its not on pbs yet. took 18 months. the app is cool but the authority requests still take forever. i get why they do it but man its brutal when you're in pain and the system moves slow. i hope the new ai stuff helps. also thanks for explaining biosimilars i finally get the difference

manish chaturvedi

November 29, 2025It is worth noting that the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme represents one of the most successful examples of state-mediated pharmaceutical access in the developed world. The systematic use of reference pricing, coupled with aggressive generic substitution protocols, has yielded an unprecedented reduction in out-of-pocket expenditures without compromising therapeutic outcomes. While the delays in listing novel agents remain a legitimate concern, the structural integrity of the system-rooted in evidence-based cost-effectiveness evaluation-demonstrates a mature, sustainable model. Other nations, particularly those with fragmented private insurance systems, would benefit from emulating its core principles: transparency, equity, and price discipline. The real challenge lies not in the mechanism, but in scaling it without sacrificing innovation.