26 Jan 2026

- 14 Comments

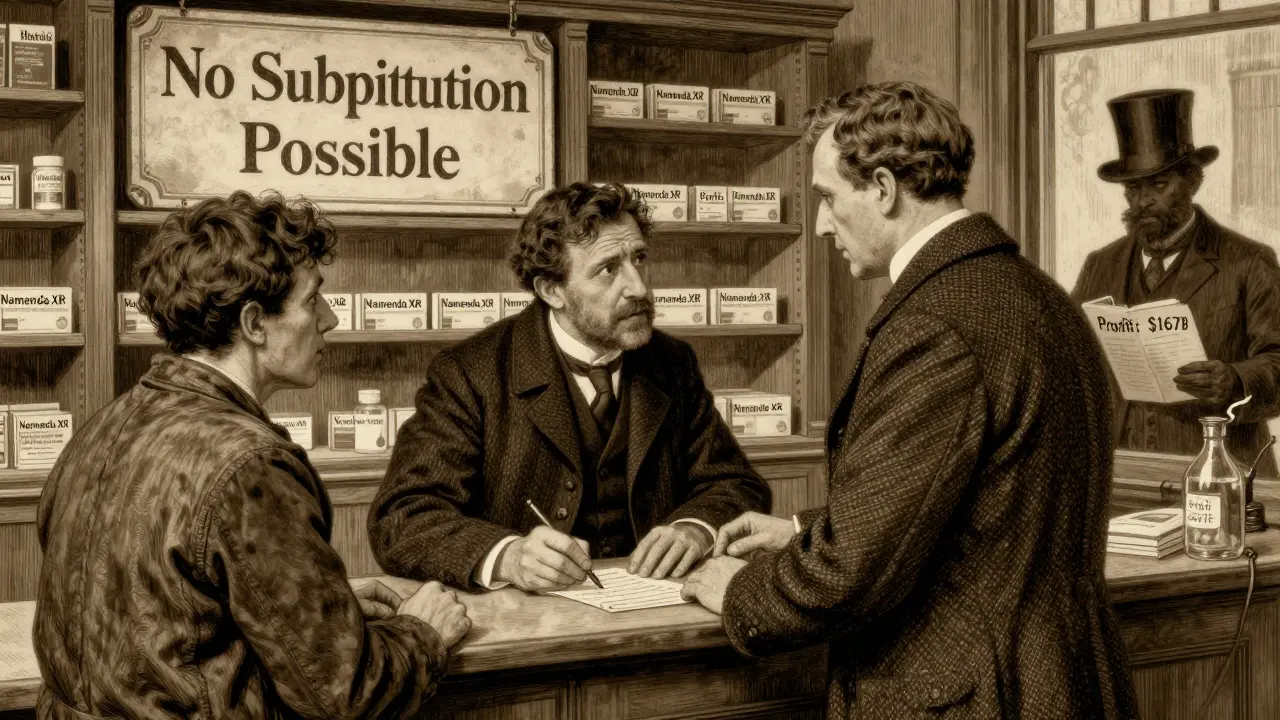

When you fill a prescription for a brand-name drug, you might expect to get a cheaper generic version instead-especially if your state law allows pharmacists to swap them automatically. But in many cases, that switch never happens. Not because generics aren’t available, but because the brand-name company made sure they couldn’t be.

How Big Pharma Blocks Generic Substitution

Pharmaceutical companies don’t wait for patents to expire quietly. When a drug’s patent is about to run out, some manufacturers launch a new version-often with tiny changes like a different shape, extended-release formula, or new coating-and then pull the original version off the market. This is called product hopping. It’s not innovation. It’s a legal loophole exploited to kill generic competition. Take Namenda, a drug for Alzheimer’s. In 2013, Actavis introduced Namenda XR, an extended-release version, and then pulled the original Namenda IR from shelves just 30 days before generics could enter. State laws allowed pharmacists to substitute the original drug with a generic. But once the original was gone, those laws couldn’t help. Patients couldn’t switch back. Doctors had to write new prescriptions for the new version, which was still under patent. Generics were locked out. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals called this out in 2016. They ruled that Actavis didn’t just sell a better drug-they destroyed the market for the generic. The court said: "The only cost-efficient means of competing available to generic manufacturers was state substitution laws. Actavis made sure those laws couldn’t be used."Why State Substitution Laws Matter

Every U.S. state has laws letting pharmacists swap brand-name drugs for generics-unless the doctor says no. These laws exist because generics are just as safe and effective, but cost 80% less. When automatic substitution works, generics take over 80% of the market within months. But product hopping breaks that system. If the original drug disappears before generics launch, pharmacists can’t substitute. Patients get stuck with the new, expensive version. And once they’re on it, they rarely go back. Switching back means another doctor visit, another prescription, more time, more hassle. That’s called transaction cost. Big Pharma counts on it. The FTC found that in cases where companies withdrew the original drug, generic market share dropped to as low as 10-20%. In cases where the original stayed on the shelf, generics captured 80%+. That’s not a coincidence. It’s strategy.The REMS Abuse Loophole

Another tactic? Blocking generic makers from getting the drug samples they need to prove their version works. The FDA requires some drugs to have a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS)-a safety program meant to control serious risks. But brand-name companies abuse it. They refuse to sell samples to generic manufacturers, claiming safety concerns. In reality, they’re just delaying competition. A 2017 study found over 100 generic companies couldn’t get samples for 40 different drugs. The cost? More than $5 billion a year in lost savings. The FTC called this a textbook case of monopolization. Why? Because it makes no economic sense unless the goal is to hurt competitors. No company would refuse to sell its own product unless it was trying to kill the market for others.

What’s Different About Namenda vs. Nexium?

Not all product-hopping cases are treated the same. Courts are split. In 2009, AstraZeneca switched patients from Prilosec to Nexium. But they kept selling Prilosec. The court said: "Adding a new product isn’t illegal. It’s competition." That made sense-patients could still choose the old one. But in Namenda, Actavis pulled the original. No choice. No fallback. That’s when courts started seeing it as anti-competitive. The key difference? Availability. If the old drug is gone, it’s not innovation-it’s exclusion. The FTC’s 2022 report flagged this inconsistency. Some judges still think generics should just spend more on ads to win back customers. But that ignores reality. Generics don’t advertise. They compete on price. And if the original drug disappears, price doesn’t matter.Suboxone: When Coercion Becomes a Legal Issue

Reckitt Benckiser didn’t just switch formulations with Suboxone. They ran ads claiming the original tablet form was unsafe-despite no evidence. Then they pushed the new film version. The FDA didn’t say the tablet was dangerous. But the company’s messaging scared doctors and patients. The FTC sued. The court found that Reckitt’s campaign was designed to coerce people into switching. It wasn’t just marketing. It was a tactic to kill the tablet market before generics could enter. In 2019 and 2020, Reckitt paid millions in settlements. The FTC forced them to stop the misleading ads and allow generic tablets to enter. This case showed that antitrust law doesn’t just cover pricing or withdrawal-it covers deception used to block competition.

Who Pays the Price?

The financial toll is massive. - Revlimid’s price jumped from $6,000 to $24,000 per month over 20 years.- Humira, Keytruda, and Revlimid alone cost U.S. payers an estimated $167 billion more than they would have in Europe, where generics entered faster.

- Teva’s Copaxone switch cost consumers $4.3-6.5 billion over two and a half years before the patent was thrown out. These aren’t theoretical numbers. They’re real costs borne by patients, insurers, Medicare, and Medicaid. Every month a generic is blocked, someone pays hundreds-or thousands-more than they should.

Enforcement Is Changing

The FTC didn’t always act. But since 2020, under Chair Lina Khan, enforcement has sharpened. - In the Namenda case, the FTC won a court order forcing Actavis to keep selling the old version for 30 days after generic entry.- The DOJ went after generic makers too, hitting Teva with a $225 million criminal fine for price-fixing in 2023.

- State attorneys general have filed suits, like New York’s case against Actavis, which led to an injunction. The FTC’s 2022 report wasn’t just a summary-it was a warning. They’re now actively pushing state legislatures to strengthen substitution laws and close loopholes. Some states are already updating rules to require manufacturers to keep selling older versions for a set time after generics launch.

John Rose

January 27, 2026It's wild how a simple switch in drug formulation can derail an entire market. I never realized pharmacists were this powerless when companies pull the original version. This isn't just about profits-it's about access. If generics can't compete because the old drug disappears, that's not innovation. That's manipulation.

And the REMS abuse? That's like locking the door to your own house and then suing anyone who tries to pick the lock. The FDA never intended it for this. Someone needs to hold these companies accountable before more patients get screwed.

Brittany Fiddes

January 28, 2026Oh please. Americans think they’re entitled to cheap drugs because they can’t handle paying for quality. In the UK, we don’t have this circus-NHS negotiates fair prices, and generics arrive without corporate theatrics. You people let pharma run wild because you’d rather complain on Reddit than vote for real reform. Pathetic.

Also, ‘product hopping’? Sounds like a toddler throwing a tantrum. If you can’t innovate, don’t whine about competition. Maybe your system is broken, not the companies.

Phil Davis

January 29, 2026So let me get this straight: if a company changes a drug slightly and pulls the old version, it’s illegal. But if they just release a new version and keep the old one, it’s fine? That’s the legal line?

Kinda makes you wonder how many other industries do this exact same thing and call it ‘upgrades.’ Think of smartphones, software, even coffee makers. We just accept it as ‘progress’-until it’s our medicine. Then suddenly, it’s fraud. Double standard much?

Anna Lou Chen

January 29, 2026Deconstructing the pharmaceutical hegemony requires a Foucauldian lens: the biopolitical control exerted through pharmacological regimes is not merely economic, but epistemic. The state substitution laws, as regulatory apparatuses, function as disciplinary mechanisms that, when subverted by capital, reconfigure patient subjectivity into passive consumers of patent-protected biocapital.

The REMS loophole isn’t a loophole-it’s a dialectical contradiction of neoliberal healthcare: safety as pretext, monopoly as telos. The FTC’s interventions, while performative, remain trapped within the very juridical framework that enabled the exploitation. True liberation? Abolish patent logic. Reimagine medicine as a commons.

Bryan Fracchia

January 30, 2026I get why people are mad, but let’s be real-pharma isn’t evil. They’re just doing what any business would do: maximize returns. The real problem is the system that lets them. We pay for R&D, but then act shocked when they try to recoup it. The solution isn’t just lawsuits-it’s public funding for generics from the start.

Imagine if the NIH funded the development of generic versions as soon as a patent neared expiration. No product hopping. No REMS abuse. Just affordable meds. It’s not fantasy. It’s what other countries do. We just refuse to pay taxes for health.

Timothy Davis

January 31, 2026Let’s break this down with actual data. The Namenda case? Actavis didn’t pull the original drug until 30 days before generic entry. That’s not ‘blocking’-that’s timing. Generic manufacturers knew the patent was expiring. They had 2+ years to prepare. If they didn’t get their product approved in time, that’s on them, not the brand.

Also, REMS abuse claims? 90% of the time, it’s generic companies refusing to sign the safety agreements-not the brand. The FTC’s numbers are cherry-picked. You want to blame monopolies? Look at the 400+ generic manufacturers that still charge $500 for a 30-day supply of metformin. That’s where the real greed is.

fiona vaz

February 2, 2026Just wanted to add-some states already have laws requiring manufacturers to keep the original version on the market for 6 months after generic approval. California and New York passed these last year. It’s working. Generic uptake jumped to 75% in those states within 90 days.

It’s not impossible. We just need more states to follow. And patients need to ask their pharmacists: ‘Is the old version still available?’ If not, ask why. Small actions add up.

Sue Latham

February 3, 2026Oh honey, you think this is bad? Wait till you see what they do with insulin. 😒

They literally change the cap color and call it ‘new and improved.’ Then they jack the price 400%. And you know what? Your insurance still covers it because you’re too lazy to switch to a cheaper brand. It’s not the pharma companies that are evil-it’s us for letting them get away with it. 🙄

Lexi Karuzis

February 4, 2026THIS IS A COORDINATED ATTACK!!!

Did you know? Big Pharma owns the FDA. They own the courts. They own your pharmacy. They even own the pharmacists’ unions! That’s why they can pull drugs off shelves overnight-because the whole system is rigged. The FTC? They’re just puppets. Look at the revolving door-former pharma lawyers now running antitrust. It’s all a lie.

And don’t get me started on the vaccines. They’re using the same playbook. You think this is about generics? No. It’s about control. They want you dependent. Mark my words: next, they’ll make your blood type require a branded drug. I’ve seen the documents. 🕵️♀️

Colin Pierce

February 5, 2026One thing people miss: pharmacists are caught in the middle. They want to substitute, but if the original drug isn’t in stock, they can’t. And if the brand company won’t sell to generics? That’s not the pharmacist’s fault.

What we need is a national database that shows which formulations are available and when they’re being discontinued. Real-time info. Then pharmacists can alert patients before the switch. Simple. No lawsuits needed. Just transparency.

Mark Alan

February 7, 2026THIS IS WHY WE NEED TO BAN BIG PHARMA!!! 🚨💸

They’re literally stealing from sick people. 😭 I had to pay $800 for my dad’s meds last month because the generic got blocked. He’s on Social Security. He doesn’t have $800. But Big Pharma does. 😡

Let’s burn their offices down. 🤬🔥 #JusticeForGenerics

Amber Daugs

February 8, 2026Ugh. I can’t believe people still fall for this. You think these companies care about you? They care about their quarterly earnings. And you? You’re just a line item. I’ve worked in pharma sales. I’ve seen the emails. ‘Target high-prescribing docs. Push new formulation. Discontinue old.’ It’s all scripted.

And don’t even get me started on the lobbyists. Every single state legislator has a pharma rep on speed dial. This isn’t a glitch-it’s the business model. Wake up.

Ambrose Curtis

February 9, 2026Look, I get it-product hopping sucks. But let’s not pretend generics are saints. I’ve seen some that look like chalk dust and cost $200. Meanwhile, the brand version? Still works fine. Sometimes the ‘generic’ is just a cheaper version with worse fillers.

And honestly? Most people don’t even know what’s in their meds. They just want the pill that works. Maybe the real issue isn’t the companies-it’s that we’re too lazy to educate ourselves. Stop blaming pharma. Start asking questions.

Linda O'neil

February 10, 2026You’re not alone. I’ve been fighting this for years. My brother has MS and got stuck on a $12,000/month drug because the generic was blocked. We fought the insurance, the pharmacy, the manufacturer. Took 8 months.

But here’s the good news: we won. We got the generic approved. It’s now $400. And guess what? He’s doing better than ever. Change is possible. Keep pushing. Talk to your reps. Share your story. They can’t ignore us forever.