21 Nov 2025

- 8 Comments

Thyroid cancer is one of the fastest-growing cancer diagnoses in the U.S., with about 44,000 new cases each year. But here’s the surprising part: most people diagnosed with it live long, healthy lives. That’s because the most common types grow slowly and respond well to treatment. The key is knowing what type you have, what treatments are right for you, and what to expect after surgery or radioactive iodine therapy.

What Are the Main Types of Thyroid Cancer?

The thyroid is a small butterfly-shaped gland at the base of your neck. It makes hormones that control your metabolism, heart rate, and body temperature. When cancer develops here, it usually starts in the follicular cells that produce thyroid hormone. There are four main types, each with different behaviors and treatments.

Papillary thyroid carcinoma is by far the most common, making up 70 to 80% of all cases. It tends to grow slowly and often spreads to nearby lymph nodes-but even then, it’s highly treatable. People under 45 with this type have a 10-year survival rate higher than 98%.

Follicular thyroid carcinoma accounts for 10 to 15% of cases. It’s more likely to spread through the bloodstream to distant organs like the lungs or bones, but it still responds well to treatment if caught early.

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) makes up only 3 to 5% of cases. It starts in the C-cells, which make calcitonin, not thyroid hormone. Some cases are inherited due to genetic mutations like RET. This type doesn’t absorb iodine, so radioactive iodine won’t work. Surgery is the main treatment.

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is rare-less than 2% of cases-but extremely aggressive. It grows fast, spreads quickly, and is often diagnosed at stage IV. Survival rates drop sharply without immediate, aggressive treatment. It doesn’t respond to radioactive iodine either.

Why Radioactive Iodine Therapy Is Used (and When It’s Not)

Radioactive iodine therapy (RAI), or I-131, has been used since the 1940s. It works because thyroid cells-both healthy and cancerous-absorb iodine to make hormones. When you swallow a capsule or liquid containing I-131, the radiation destroys any remaining thyroid tissue after surgery.

It’s most effective for papillary and follicular cancers because they still have the sodium-iodide symporter-the protein that pulls iodine into the cells. Anaplastic and medullary cancers don’t have this protein, so RAI won’t work on them.

Doses vary from 30 to 200 millicuries (mCi). For low-risk patients, studies like the HiLo trial show that 30 mCi works just as well as 100 mCi for destroying leftover tissue. That means less radiation exposure and fewer side effects. Many doctors now avoid RAI altogether for small tumors under 1 cm without high-risk features.

Before RAI, you need to raise your TSH levels so your body craves iodine. This is done in two ways: either stop taking thyroid hormone for 2-4 weeks (which causes fatigue, weight gain, and brain fog) or get injections of recombinant human TSH (Thyrogen®), which avoids hypothyroidism but costs more.

After treatment, you’ll need to avoid close contact with others for a few days because you’re temporarily radioactive. You’ll also follow a low-iodine diet for 1-2 weeks before treatment to make your cells more hungry for the radioactive iodine. Many patients say this diet is harder than the surgery itself-no dairy, eggs, bread with iodized salt, seafood, or even some medications.

Thyroidectomy: What Surgery Actually Involves

Surgery is the first step for almost all thyroid cancers. The type of operation depends on the cancer’s size, type, and whether it’s spread.

A lobectomy removes just one side of the thyroid. It’s often enough for small, low-risk papillary cancers. Recovery is quick-many patients go home the same day. The incision is about 4 to 6 cm long.

A total thyroidectomy removes the entire gland. This is standard for larger tumors, cancers that have spread to lymph nodes, or for patients who will get RAI. The incision is 6 to 8 cm. The surgery takes 2 to 3 hours. Surgeons now routinely use nerve monitoring to protect the recurrent laryngeal nerves that control your voice. Even so, 5 to 10% of patients have temporary hoarseness, and 1 to 3% end up with permanent voice changes.

Another risk is damage to the parathyroid glands, which sit behind the thyroid and control calcium levels. If they’re injured or removed, you’ll need calcium and vitamin D supplements long-term. About 20% of patients have temporary low calcium after surgery; 5 to 10% have it permanently.

There are newer techniques like transoral (through the mouth) or robotic surgery, but these aren’t widely used. Open surgery still has the lowest complication rate-8.9% versus 12.4% for robotic approaches. Most surgeons prefer the traditional method because they can see everything clearly.

What Happens After Surgery and RAI?

After a total thyroidectomy, you’ll need to take levothyroxine for life. This replaces the thyroid hormone your body can’t make anymore. The goal isn’t just to feel normal-it’s to suppress TSH, which can stimulate any leftover cancer cells. For intermediate-risk patients, doctors aim for a TSH level between 0.5 and 2.0 mIU/L.

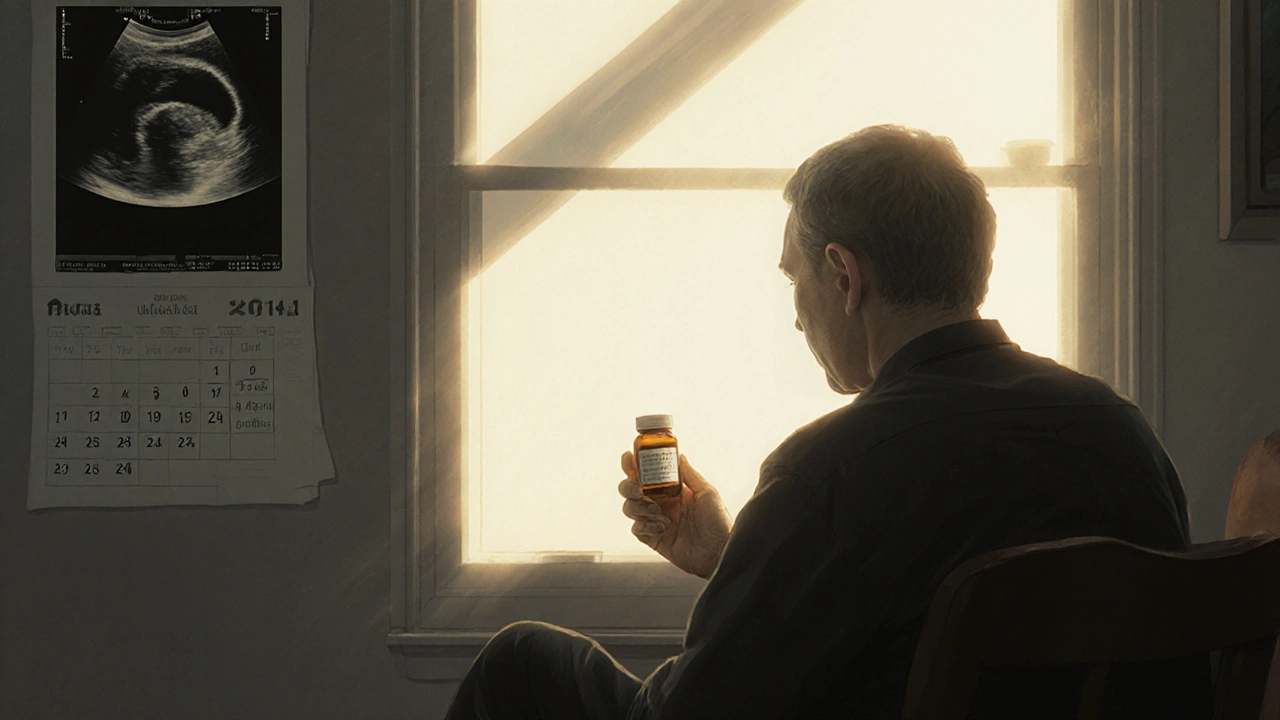

Many people still feel off even with perfect TSH numbers. A 2023 survey of over 1,200 thyroid cancer survivors found that 68% still had symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, or weight gain. Some blame the medication, others blame the loss of their thyroid’s natural hormone balance. A small group of patients now take T3 supplements along with T4, though this isn’t standard yet.

Calcium levels must be checked regularly, especially in the first few weeks after surgery. Normal range is 8.5 to 10.2 mg/dL. If it drops below 8.0, you may need intravenous calcium or higher doses of supplements.

Follow-up includes blood tests for thyroglobulin (a protein made only by thyroid tissue) and neck ultrasounds. If thyroglobulin rises after treatment, it could mean cancer is back. RAI scans or PET scans may follow.

Is Overtreatment a Real Problem?

Yes-and it’s becoming a major concern in thyroid cancer care. Up to 30% of patients with papillary thyroid cancer get more treatment than they need. That means total thyroidectomies when a lobectomy would’ve been enough, or RAI when it’s unnecessary.

Why? Because doctors often feel pressured to do something aggressive. And patients, scared of cancer returning, sometimes ask for the “most thorough” option.

But research shows that for tiny tumors under 1 cm with no spread or aggressive features, active surveillance is safe. A 10-year study in Japan found only 3.8% of these small cancers grew or spread. Many patients avoid surgery entirely and just get yearly ultrasounds.

Guidelines now support this approach. The 2015 American Thyroid Association guidelines say: don’t give RAI for small, low-risk tumors. Don’t remove the whole thyroid unless there’s a clear reason. And don’t rush into surgery for microcarcinomas without discussing observation.

The goal now isn’t just survival-it’s quality of life. Avoiding lifelong hormone replacement, preventing voice changes, and reducing the stress of RAI prep are just as important as beating cancer.

What’s New in Thyroid Cancer Treatment?

Thyroid cancer treatment is changing fast. In 2018, the FDA approved dabrafenib plus trametinib for BRAF-mutant anaplastic thyroid cancer. It boosted median survival from 5.3 to 10.8 months. That’s huge for a disease that used to kill within months.

For medullary cancer with RET mutations, selpercatinib (approved in 2021) shrinks tumors in most patients. It’s a targeted pill, not chemo. And for RAI-resistant cancers, drugs like selumetinib are being tested to “redifferentiate” tumor cells-making them absorb iodine again. In one trial, 54% of patients regained iodine uptake after treatment.

Future tools include liquid biopsies, where a blood test detects cancer DNA instead of waiting for a tumor to show up on a scan. Immunotherapy is also being explored, especially for anaplastic cancer. But so far, it hasn’t delivered the same results as in melanoma or lung cancer.

One big issue remains: access. Rural patients have 28% higher death rates than urban ones. Why? They’re less likely to see an endocrinologist or surgeon who specializes in thyroid cancer. Getting the right care early makes all the difference.

What Should You Ask Your Doctor?

If you’ve been diagnosed, here are five questions to ask:

- What type of thyroid cancer do I have, and what’s the stage?

- Do I need a lobectomy or total thyroidectomy? Why?

- Will I need radioactive iodine? If so, what dose and why?

- What are the chances of voice changes or low calcium after surgery?

- Can we consider active surveillance instead of surgery?

Don’t feel rushed. Take time to get a second opinion, especially if surgery or RAI is recommended for a small, low-risk tumor. You have options. And the best treatment isn’t always the most aggressive one.

Is thyroid cancer curable?

Yes, most types of thyroid cancer are highly curable. Papillary and follicular cancers have 10-year survival rates above 95% when caught early. Even with spread to lymph nodes, many patients live normal lifespans with proper treatment. Anaplastic thyroid cancer is the exception-its survival rate is low, but new targeted therapies are improving outcomes.

Can you live without a thyroid?

Absolutely. People live full, healthy lives without a thyroid by taking daily levothyroxine. The hormone replacement is simple, inexpensive, and effective. The challenge isn’t survival-it’s managing side effects like fatigue, weight changes, or brain fog, which some people experience even with perfect TSH levels.

Does radioactive iodine therapy make you radioactive to others?

Yes, for a few days after treatment. You’ll need to avoid close contact with children and pregnant women, sleep alone, and not share utensils or towels. Most hospitals give you detailed instructions. The radiation fades quickly-in 7 to 10 days, you’re no longer a risk to others. The dose you receive is carefully calculated to destroy thyroid tissue without harming other organs.

Why do some people gain weight after thyroid cancer treatment?

Weight gain after thyroid cancer treatment is common but not inevitable. It can happen if your levothyroxine dose isn’t quite right, or if your metabolism slows after thyroid removal. Some people also gain weight during the hypothyroid phase before RAI. The key is regular TSH testing and adjusting your dose. But even with perfect levels, some people still struggle with weight-possibly due to changes in how their body uses energy after losing the thyroid.

Is thyroid cancer hereditary?

Most cases aren’t. But about 5 to 10% of medullary thyroid cancers are inherited due to mutations in the RET gene. If you have MTC, your doctor may recommend genetic testing. For papillary or follicular cancer, family history matters less, though having a close relative with thyroid cancer slightly increases your risk. Routine screening isn’t needed unless there’s a known genetic syndrome.

fiona collins

November 23, 2025Thank you for this incredibly clear breakdown. I’ve been researching this since my diagnosis last month, and this is the first time I’ve felt like someone actually explained it without overwhelming me.

Patricia McElhinney

November 24, 2025Actually, you're grossly underestimating the dangers of active surveillance. I've seen patients with 'microcarcinomas' turn into metastatic disease in 18 months because doctors were too lazy to remove the whole gland. The ATA guidelines are a joke-based on Japanese data where thyroid cancer is biologically different. In the U.S., we don't have that luxury. If you're not getting a total thyroidectomy, you're gambling with your life. And don't get me started on the low-iodine diet-it's not 'hard,' it's mandatory. If you can't follow a diet for two weeks, maybe you shouldn't be getting treated at all. Also, you misspelled 'thyroglobulin' twice in this post. I'm not even mad, just disappointed.

Dolapo Eniola

November 25, 2025Bro, this is why Africa needs to stop copying Western medicine! We don't need RAI or robotic surgery-our ancestors healed with herbs and prayer. Why spend $20k on a thyroidectomy when you can drink bitter leaf tea and chant over your neck? I’ve cured three cousins with just ginger and a goat’s skull. Also, your ‘TSH levels’? That’s just Big Pharma’s way of keeping you on pills forever. Wake up! 🌿🪔

Agastya Shukla

November 27, 2025Very thorough. One point I’d add: the sodium-iodide symporter (NIS) expression isn’t binary-it’s a spectrum. Some papillary cancers downregulate NIS over time, which explains why some patients who initially responded to RAI later become refractory. That’s why emerging therapies like selumetinib aim to re-induce NIS expression, not just kill cells. Also, the 2023 survey on persistent symptoms-was that self-reported or biomarker-validated? If self-reported, it’s likely confounded by anxiety and hypothyroidism misattribution. Still, important data.

Pallab Dasgupta

November 28, 2025LET ME TELL YOU SOMETHING. I WAS DIAGNOSED WITH PAPILLARY THYROID CANCER AT 28. I DID THE WHOLE THING-TOTAL THYROIDECTOMY, RAI, LOW-IODINE DIET, THE WORK. I ATE NOTHING BUT BROCCOLI AND CHICKEN BREAST FOR TWO WEEKS. I WAS SO TIRED I COULDN’T WALK TO THE FRIDGE. BUT HERE’S THE THING-I’M STILL HERE. I’M HIKING MOUNTAINS. I’M TRAVELING. I’M LIVING. PEOPLE SAY ‘YOU’RE LUCKY’-NO. I’M STRONG. I DID THE WORK. AND IF YOU’RE READING THIS AND YOU’RE SCARED? YOU CAN DO THIS TOO. YOU AREN’T BROKEN. YOU’RE A SURVIVOR. 💪🔥

Josh Zubkoff

November 29, 2025Okay, so let’s unpack this. You spent 1,200 words telling us that thyroid cancer is ‘curable’-but you didn’t mention that 1 in 4 patients develop depression post-op. Or that 30% of those on levothyroxine report ‘brain fog’ so severe they can’t hold down jobs. And you glossed over the fact that the entire industry profits off lifelong hormone replacement-levothyroxine is a $1.2B market. You didn’t even touch on the psychological trauma of being told ‘you’re fine’ while your body feels like it’s rotting from the inside. And the RAI isolation? That’s not just ‘avoiding contact’-that’s being locked in a hotel room like a radioactive leper while your partner sleeps in another room because the hospital says you might ‘contaminate’ your own child. This isn’t medicine. It’s a trauma factory dressed in white coats.

Ellen Sales

December 1, 2025I’ve been living with this for 12 years… and I still cry when I see my thyroid scan results… I still wonder if I’m enough… if I’m doing enough… if my body will ever feel like mine again… I take my pill every morning… and I still feel like I’m missing something… I don’t know what it is… but I miss it…

Rachel Villegas

December 1, 2025This is exactly why I started a support group for thyroid cancer survivors. We meet every Thursday. No judgment. Just coffee, silence, and sometimes tears. If you’re reading this and you’re alone, you’re not. Reach out. We’re here.